The Japanese Canadian Experience

History of Japanese Immigration

Japanese immigration to Canada was first officially recorded in the 1870s, with significant number arriving by the 1890s. Most settled in British Columbia, where they worked mainly in fishing, mining, sawmills, and farming. Japanese Canadians, like other Asian immigrants, were seen as cheap labour and faced widespread discrimination from white settlers, labour unions, and politicians.

Throughout the years, the Canadian government had implemented several restrictions that also impacted the Japanese:

- In 1872, the Qualification and Registration of Voters Act prevented both Indigenous and Chinese people from voting in provincial elections in BC. This also had the effect of barring them from serving on juries, pursuing careers in law, medicine, accounting and pharmacology, and voting in federal elections since these all required having their name on the voting roll.

- The exclusion was extended to the Japanese in 1895.

- After the Anti-Asian riot in Vancouver in 1907, Canada negotiated an informal agreement with Japan to limit immigration to 400 men per year (later reduced to 150 in 1928).

Despite these obstacles, by the 1930s the Japanese population in Canada had grown to over 22,000 with thriving communities in Steveston, Vancouver, and other coastal towns. They built cultural centres, Japanese-language schools, Buddhist temples, and owned a large share of the salmon fishing fleet on the Pacific coast.

Roles of the Japanese

Japanese Canadians made major contributions to British Columbia's economy:

- In fishing, they operated a significant portion of the region's boats and formed the cannery labour.

- In agriculture, they turned marginal land into productive farms, often growing strawberries and vegetables.

- Many also worked as loggers, domestic workers, storekeepers, and in small trades.

However, this success generated resentment. Japanese Canadians were increasingly portrayed as economic competitors and racial outsiders, even if they were born in Canada.

Views on the Japanese Canadians

Before World War II, anti-Japanese sentiment was already deeply rooted in British Columbia. Many white residents viewed Japanese Canadians as permanently foreign, regardless of citizenship or language. Organisations like the Native Sons of British Columbia actively campaigned for their removal and exclusion.

After Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, racial fears turned into official action. Although there was no evidence of sabotage or disloyalty by Japanese Canadians, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King invoked the War Measures Act, which resulted in one of the most sweeping civil rights violations in Canadian history.

Forced Removal and Dispossession

What Happened?

On February 24, 1942, Order-in-Council 1486 designated a 100 mile exclusion zone along the British Columbia coast and ordered the forcible removal of over 22,000 Japanese Canadians, the majority of which were Canadian-born citizens. Under the War Measures Act, they were declared "enemy aliens" and removed from their homes often with only 24 hours notice.

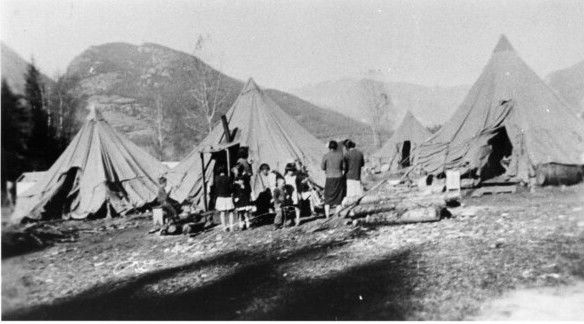

Men were often separated from their families and sent to road-building camps, internment sites, or even prison camps in Alberta and Ontario. Women, children, and the elderly were relocated to hastily constructed "relocation centres" in interior British Columbia- usually abandoned mining towns or makeshift shacks in the wilderness. Those who were willing were moved to work on farms in the prairies.

Unlike in the US, where many internees returned to their homes after the war, the Canadian government took a more drastic step. Order-in-Council 469, issued on January 16, 1943, authorised the Office of the Custodian of Enemy Property, who had confiscated Japanese Canadian property; under the guise of holding it in trust, to sell it without consent. This included homes, farms, businesses, fishing boats, vehicles and personal belongings.

This was a calculated move to eliminate the Japanese presence from the West Coast since they would have nothing to return to.

Life in the Camps

Conditions in the camps were harsh. Families lived in small, drafty cabins or converted barns, often without running water or insulation. Winters were bitterly cold, and fuel and supplies were limited. Sanitation was poor, and disease was common. Respiratory infections like pneumonia and bronchitis were common in the cold winters, especially among the children and the elderly. Gastrointestinal diseases such as dysentery and diarrhea spread easily. Over time, camp hospitals and volunteer medical teams improved conditions somewhat, but many suffered long-term health effects due to prolonged exposure, malnutrition, and stress.

Despite these conditions, internees worked to maintain a sense of community. They organised schools, worship services, cultural activities, and small local industries. Children received basic education in makeshift classrooms, while adults worked in nearby farms or did manual labour for meagre wages.

Japanese Canadians were forbidden from leaving the camps without permission. Many had to sign agreements to move east of the Rockies if they wished to be released. This policy was intended to disperse and assimilate them.

Treatment of Other Axis Immigrants

During World War II, the Canadian government also interned German and Italian Canadians, but their treatment was markedly different:

- About 850 German and 600 Italian Canadians were interned, mostly individuals suspected of fascist sympathies or associations and not entire communities.

- There was no mass removal or confiscation of property for German or Italian populations.

- Unlike Japanese Canadians, German and Italian Canadians could often retain property and return home after release.

This disparity reveals how racism, not just wartime security concerns, drove the internment of Japanese Canadians.

Post Internment

What Were the Consequences?

Even after World War II ended in 1945, Japanese Canadians were not allowed to return to the West Coast until 1949. In the meantime, they were pressured to move east or repatriate to Japan, regardless of whether they had ever lived there. Nearly 4,000 were deported under duress, including Canadian-born citizens.

By the time the return ban was lifted, the damage was done:

- Entire communities were erased. For example, the Powell District Area, otherwise known as Japantown, was once a thriving part of Vancouver. Now, only a few landmarks remain.

- Families were scattered across the country, often force to rebuild in unfamiliar cities like Toronto, Montréal, and Winnipeg.

The economic, emotional, and psychological effects of internment lasted for generations. Many Issei died in poverty. Nisei struggled with identity, mistrust of institutions, and silence within their own families. The trauma was deeply internalised, and for decades, Japanese Canadians did not speak publicly about their experience.

That began to change in the 1970s and 80s, when a new generation began demanding an apology and compensation. After years of the community organising, testimonies, and negotiations, the government finally acquiesced.

In 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney issued a formal apology and announced a redress agreement that included:

- $21,000 in compensation to each surviving internee.

- The restoration of citizenship rights and formal recognition of the the injustice.

- Funding for community initiatives and education.

Comparisons with the United States

While both the United States and Canada interned their Japanese populations during World War II, the experience of Japanese Canadians was much worse:

- Property Seizures: In the US, much property was lost, but families sometimes could recover land and belongings. In Canada, the government confiscated and sold Japanese Canadian property without the owners' knowledge or permission.

- Return Restrictions: Japanese Americans were allowed to return home starting in 1945. Japanese Canadians were banned from the West Coast until 1949 in a plan to disperse and assimilate them.

- Scale: Canada interned about 22,000 people, nearly the entire Japanese Canadian population. In contrast the US interned about 120,000, but this was roughly two-thirds of Japanese American population.

- Military Service: In the US, Japanese Americans served in the military with distinction, most notably in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. In Canada, Japanese Canadians were initially barred from military service, and only a few were later permitted to enlist under British pressure. Many of those that had joined when Canada declared war on Germany in 1939 were demoted to routine service on Canadian bases after Pearl Harbor.

Both cases illustrate how fear, racism, and political expediency can override democratic principles and devastate innocent communities.